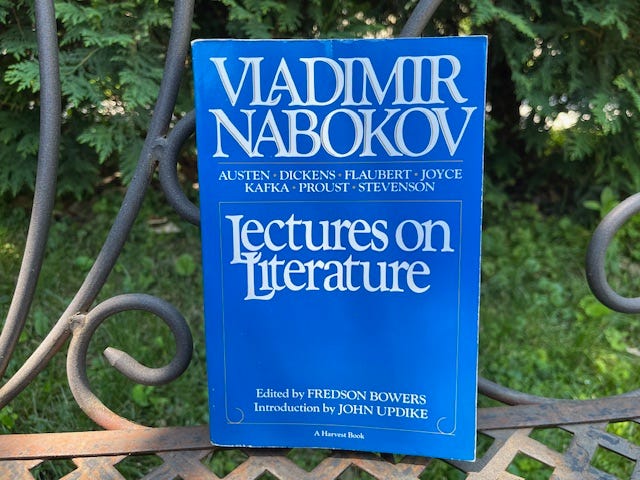

Back when I was a high school student beginning to explore the somewhat intimidating world of “real” literature, I came across the books of lectures that Vladimir Nabokov had given. These books – Lectures on Literature, Lectures on Russian Literature, and Lectures on Don Quixote – were posthumously collected and edited versions of Nabokov’s lectures given while he was teaching at Wellesley and Cornell, before the smash success of Lolita allowed him to ditch academic life forever.

Coming across these books early meant that they left an indelible imprint in my mind. When I read literary works later on – whether Nabokov had discussed them or not – I would naturally tend to apply Nabokov’s method of analysis. I think what most appealed to me was that he took a stance that came about as close to the purely aesthetic as possible. That is, the only thing that really mattered with a piece of literature was that it stood up as a work of art; everything else – the political, the personal, the sociological – was superfluous. Here’s how he summarized his approach:

We should always remember that the work of art is invariably the creation of a new world, so that the first thing we should do is to study that new world as closely as possible, approaching it as something brand new, having no obvious connection with the worlds we already know.

He thought it was foolish to read Dickens in order to get an understanding of Victorian England, and pointless to read Tolstoy if you wanted insight into the Russian aristocracy of his time. He was also allergic to the notion that literature should convey “great ideas.” Personally, I can agree with the primacy of the aesthetic approach to literary works, but that doesn’t rule out appreciation of their other qualities.

That said, even at an early and naïve stage, some alarm bells went off in my head. One annoyance was Nabokov’s dismissal (I would even say “trashing”) of a whole range of well-known writers. Off the top of my head, I can recall hostile, dismissive comments about Balzac, Stendhal, Mann, Rilke, Dostoevsky, O’Neill, Faulkner, Hemingway, and Conrad, and that probably doesn’t exhaust the list. I’ve only read one in-depth negative dissection by Nabokov of an author he didn’t like – the chapter on Dostoevsky in Lectures on Russian Literature – and I remember not being at all convinced by it, though I think he was on to something when he pointed to Dostoevsky’s humor as one of his best qualities.

Somehow, I suspected that these trashings of the classics were not based on sustained engagement with them. There’s an anecdote in Brian Boyd’s biography where Nabokov is giving a withering critique of the Laurence Olivier film version of Hamlet. Somebody asks him if he’s actually seen the film, to which he says something like: “Do you really think I’d watch a film as bad as the one I just described?” Nabokov, in fact, struck me as a writer who hadn’t found much literature he actually enjoyed; but what he did like, he really liked. He quotes a line by Flaubert: “What a scholar one might be if one knew well only some half a dozen books.” It’s this “half a dozen” (or however many) that he deemed worthy of his attention. And he had worked out his own idiosyncratic system of aesthetics, which he used when undertaking his critiques.

What all this means is that I think it’s time for a re-reading. Therefore, I’m going to read Lectures on Literature again, giving my thoughts on Nabokov’s thoughts on the books we both have read. I was pleased to see that Nabokov agrees with me on the value of re-reading:

Curiously enough, one cannot read a book: one can only reread it. A good reader, a major reader, an active and creative reader is a rereader. And I shall tell you why. When we read a book for the first time the various process of laboriously moving our eyes from left to right, line after line, page after page, this complicated physical work upon the book, the very process of learning in terms of space and time what the book is about, this stands between us and artistic appreciation.

Perhaps, with the advent of audiobooks, he would have reconsidered this opinion, but in general I think he’s right. More importantly, when you’re dealing with complex works, you need those re-readings to uncover and master the complexities. A really good book is like a well with no bottom; you can keep bringing up the water and never run dry.

Before I start analyzing, I have to issue one caveat. Nabokov covers seven books in this course. One, Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park, I haven’t read at all. Another – that seemingly endless thing by Proust – is something I’ve only nibbled at here and there. So I’m going to skip those lectures. That leaves these five, all of which I’ve read:

Charles Dickens, Bleak House

Gustave Flaubert, Madame Bovary

Robert Louis Stevenson, Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde

Franz Kafka, The Metamorphosis

James Joyce, Ulysses

We have two enormous labyrinthine mega-novels (Bleak House and Ulysses), two novellas (Jekyll & Hyde and The Metamorphosis), and one “normal-length” novel (Madame Bovary). In the next post in this series, I’m going to delve into Nabokov’s take on Bleak House. Stay tuned!