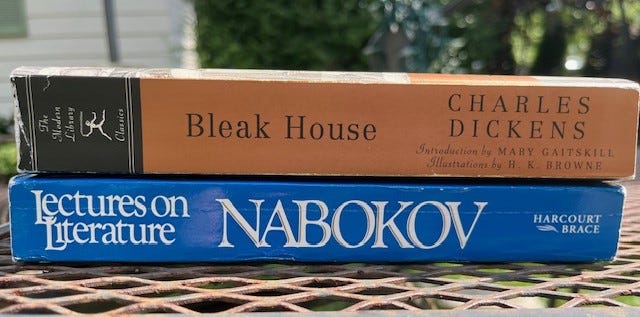

Bleak House consists of 67 chapters, which add up to 861 pages in my Modern Library edition. Its primary subject is a lengthy, convoluted lawsuit that warps the lives of the people connected with it. To tackle this subject, Dickens wrote a lengthy, convoluted book, which essentially consists of two interlocking books. One is a third-person narrative told in the present tense1 (let’s call this strand “3P”). The other is Esther Summerson’s narrative, a first-person story told in the past tense (“ES”). Thus, we have a double disjunction that runs throughout the story, which begins with 3P and ends with ES. These two perspectives alternate at regular intervals (every few chapters) throughout the book.

Nabokov’s overall analysis is more that of a craftsman than of a critic. This is natural enough – a novelist writing about how a novel is put together. Curiously however, he doesn’t comment much on the significance of this narrative bifurcation. While he speaks about Dickens’ intentions from time to time, he doesn’t say why he chose to tell the story in this way. I can think of one – it allows the reader to get multiple perspectives. 3P is the broad lens, and the one that allows Dickens to indulge in the rhetorical flourishes that famously color his style. ES slants toward the domestic, restricted, and subdued.

However, Nabokov points out something I hadn’t noticed previously: namely, that over the course of the story, the two narrators start to merge in style – specifically, ES starts to sound like 3P, and by the end of the book, they are almost indistinguishable (“Stylistically, the whole book is a gradual sliding into the matrimonial state between the two”). ES starts out as what he calls “baby style” (this is Dickens, a man entering middle age, inhabiting a young woman of about twenty), but the author’s more colorful and complex mature style keeps breaking in. Nabokov considers this a misjudgment or oversight on the part of Dickens, but I’m not so sure. A person can have more than one mode of expression, and this stylistic merging may be a deliberate choice on Dickens’ part – perhaps to show Esther’s maturation as she confronts the complicated outside world?

From this lecture, I picked up a couple of useful terms, which Nabokov claims he invented. The first is sifting agent. Nabokov defines this as a character “who sifts the story through his-her own emotions and notions.” The second is perry, which he supposedly made up from periscope, although a more natural source would be words like peripatetic and peregrinate, terms related to moving from place to place. This refers to characters whose purpose is “to visit the places which the author wishes the reader to visit and meet the characters whom the author wishes the reader to meet.” Esther, in addition to her role as one of the main characters, also functions as both a sifting agent and a perry. I have never heard anyone else use these terms; I hope they will come in handy at some point.

Nabokov makes some fairly obvious points about Dickens’ use of names – they tend to be comic devices designed to evoke the nature of a character (examples: Krook, Flite, Smallweed). This is part of the “shadow” following a person that he talks about (“Every character has his attribute, a kind of colored shadow that appears whenever the person appears”). But on this issue of nomenclature, he barely scratches the surface. What he doesn’t talk about is more interesting.

First, both in Bleak House and elsewhere, Dickens follows a general habit of giving normal names to his major characters, while his minor characters often get stuck with comical or ridiculous names, like Pumblechook or Turveydrop. There is also Dickens’ use of names as functional elements in the story. One character is Mr. George, a former military man and now the owner of a shooting gallery. He is referred to regularly as “Mr. George,” and his establishment is called George’s Shooting Gallery, which implies that this is his last name. In fact, it turns out to be his first name, and Dickens withholds his last name until late, when it becomes time to reveal the identity of his mother. A similar act of withholding concerns the character known as Nemo (“Nobody”), who sets a large part of the plot in motion; the anonymous monicker is designed to hide his identity at the beginning.

The spontaneous human combustion of Krook is a scene that everyone who has read this book remembers. Nabokov quotes it at length. The long quotation brings to life the gruesome nature of it, which is reminiscent of schlock horror movies. Krook doesn’t just go up in flames; little flakes and gobs of him float around in the air and land on all kinds of things, including other characters, smearing them with human grease. If you’re looking for some symbolic significance, I suppose you could say that Krook is corrupting and befouling everything and everyone around him, but this seems like a superfluous comment; the shudder-making effect this scene creates is memorable enough.

Since spontaneous human combustion is considered a pseudo-scientific belief by medical experts, Nabokov gets another chance to point out that even realistic novels are essentially “fairy tales.” Dickens, in his introduction, defends his decision to have Krook die this way by pointing to some historical evidence. Nabokov considers this irrelevant, because “the work of art is invariably the creation of a new world.” What matters is not the opinion of the medical community, but whether the scene makes artistic sense: “We feel it all physically, and it does not, of course, matter a jot whether or not a man burning down that way from the saturated gin inside him is a scientific possibility.”

Nabokov doesn’t state this explicitly, but Bleak House validates his claim that real reading is re-reading. An early description of Krook mentions “the breath issuing in visible smoke from his mouth, as if he were on fire within.” At first glance, this looks like a minor detail designed to embed Krook stylistically in his smoky, foggy environment. On a subsequent reading, you realize that it is also a premonition of Krook’s death; the detail is suddenly not as minor as you thought.

Finally, notwithstanding his disdain for injecting sociology into literary analysis, Nabokov points to the note of compassion in Dickens’ work as an indication of societal evolution: “Despite all our hideous reversions to the wild state, modern man is on the whole a better man than Homer’s man, homo homericus, or than medieval man.” More bluntly, caring about kids or poor people is not something you see a lot of in ancient or medieval literature.

Summary: Many or most of the things Nabokov points out are fairly obvious, at least to anyone paying attention: the Chancery/lawsuit theme, the role played by miserable children, the detective story woven throughout the text, the author’s various stylistic flourishes, and so on. Stating the obvious is a sensible thing when dealing with such a labyrinthine novel, where one risks drowning in the details. Beyond the obvious, Nabokov is giving you the “architect’s view” of the house. Dwelling in Bleak House as readers, we can see the designs and effects, the results of long-term planning. But the architect works from a blueprint, which is essentially a picture of intentions. Nabokov focuses on the long-term planning, how this reflects Dickens’ authorial intentions, the way the various structural elements connect, and how solid those connections are. There are places where Nabokov points out the weakness of some of these elements, like a plumber telling you that your sump pump is in danger of conking out. This is very much the perspective of a writer who has already written several novels and has had to confront these issues himself.

Is this the earliest instance of a present-tense novel narrative? This is something I don’t recall being common until fairly late in the 20th century. Any literary scholars wanting to weigh in?