I had taught myself German out of Teach Yourself German, and I recognised several words in this sentence at once:

It is truly something and something which the something with the something of this something has something and something, so something also this something might something at first something.

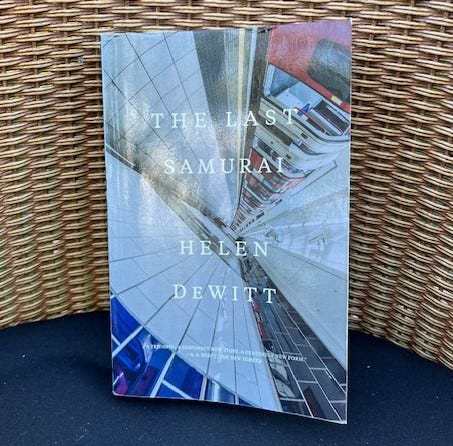

A few months ago, a list of the 100 best books of the century so far was published by the New York Times. It occasioned a lot of commentary on Substack, as such lists tend to do. I was glad to see that The Last Samurai had made the list. On my first reading of the book, I thought: “Finally, a contemporary novel that lives up to the hype.” I was also aware that the book had acquired a devoted, almost cult-like following in the years after its first publication in 2000, when it had fallen out of print and become hard to find (New Directions republished it in 2016).1 The list reminded me that a re-reading was in order.

The term Bildungsroman literally means “novel of education,” and The Last Samurai may be the ultimate achievement in this sense, since education – the theory and practice thereof, as well as its effects – is at the center of the book from beginning to end. Sibylla, an American expat in London with a Classics degree from Oxford,2 is raising her son Ludovic (“Ludo”), who is the product of a brief dalliance with a well-known travel writer. Despite her elite credential, she works at a dead-end office job, typing up old periodicals for archival purposes (“I should be typing Advanced Angling as they want it back by the end of the week, but it seems important to preserve my sanity”). Hampered by the obstacles of everyday life, she pours her intellect into educating Ludo. He is a prodigy of rare gifts. Here’s what he’s doing at the age of six:

I had to read 8 books of the Metamorphoses and 30 stories in the Thousand & One Nights and I Samuel and the Book of Jonah and learn the cantellation and do 10 chapters of Algebra Made Easy and now I just have to finish this book and one book of the Odyssey.

All of this in the original languages, of course. To counteract the absence of a father in the house, Sibylla and Ludo engage in repeat viewings of The Seven Samurai because it depicts multiple adult male role models.

The story hinges on a couple of connected ideas. The first is play, which is introduced as a key aspect in the prologue, which deals with Sibylla’s family history. This is even reflected in the name “Ludo” (Latin for “I play”). Ludo tends to treat the acquisition of knowledge as a game; master the rules and you can learn anything, a method that applies especially to subjects like languages and mathematics. (The way the narrative is structured ensures that you, the reader, can play along with Ludo.) The second idea is the quest for knowledge itself, which indeed is often characterized by elements of play. Beyond that, the quest for knowledge plays out in an obsessive fashion that gives the narrative most of its drive.

An important early part of Ludo’s quest for knowledge is finding out the name of his biological father. When he learns the name, he is disappointed to discover who it is; he’s not quite the father he had hoped for. But why shouldn’t an enterprising boy adopt a father, rather than the other way around? So Ludo goes looking for a father who is an intellectual match for him.

Ludo’s candidates for his ideal father all have certain characteristics in common. They are intellectually brilliant; they are relentlessly driven by the quest for knowledge; and they are willing to reckon with all kinds of dangers and difficulties in order to undertake that quest. Often, the quest takes them into situations they didn’t expect, involving difficult decisions and ethical quandaries. In order of introduction, these potential fathers are:

Kenzo Yamamoto: a virtuoso pianist who, building on the insight that the piano is basically a percussion instrument, becomes obsessed with experiencing “percussion in its purest form”;

Hugh Carey: a headstrong classicist who, having learned that a Central Asian tribe speaks an unknown language that they have carefully guarded from outsiders, sets out to find the tribe;

George Sorabji: an astronomer and mathematician with a complicated, peripatetic life story, who stars on a successful TV show about science;

The Painter: a painter (no name given) fascinated by “pure colour”; he flies to the Canadian Arctic to experience white, visits a slaughterhouse to see the reddest possible red, etc.;

Mustafa Szegeti: a genius at gambling and card-playing, who exploits his gift for bluffing and deception for humanitarian purposes; and

Red Devlin: A travel writer and adventurer, but a much better one than Ludo’s biological father.

To these men, add Ludo’s real father, and you arrive at the magic number seven. Ludo himself is a specific kind of samurai: a ronin, that is, a samurai without a lord or master. The father figures he approaches are intellectual adventurers and risk-takers who seem to evoke a different time. They remind me of characters like Sir Henry Rawlinson, who spent years recording and deciphering cuneiform inscriptions in Old Persian while perched precariously in front of a sheer rock face. This risk-taking (what one might call “extreme scholarship”) gives the story a charge that you wouldn’t get from today’s office-bound, bureaucratized scholars. It also produces an old-fashioned feeling by bridging the divide between intellectuals and “men of action” that widened into a chasm in the last century or so.

A further characteristic that unites several of the potential fathers is their engagement with youth – something that one would naturally expect of a father. Sorabji and Yamamoto both find themselves helping young men in difficult situations, in Latin America and Africa respectively (one story ends happily, the other doesn’t). Carey, via an extreme exercise of intellect and will, actually saves the life of a boy while on his Central Asian linguistic adventure.

Ludo’s quest also constitutes a real-life reenactment of some aspects of Kurosawa’s film, most obviously the recruitment scenes early on. To underscore this, Ludo peppers his adventures with key phrases from the film (“If we had fought with real swords I’d have killed you” and “A good samurai will parry the blow” are among the most commonly cited).

The book is divided between Sibylla’s first-half first-person narrative and Ludo’s second-half one, with a more formal quasi-third-person style taking over during the various “father” passages, where life stories have to be told. DeWitt is skillful at distinguishing the two narrative voices. Sibylla writes in a quick, clipped style, full of ampersands and abbreviations; it suggests a slightly neurotic, frantic personality. Ludo manages to sound innocent and authoritative at the same time, in a precocious-kid manner, as he regurgitates the knowledge he has absorbed and meditates on the world he finds himself in.

It’s probably not a coincidence that a samurai from Kurosawa’s film who resonates forcefully in the book is Kyuzo, the ascetic swordsman who “is interested in nothing but the perfection of his art.” Furthermore, I suspect that the name of Sorabji may be derived from the eccentric composer who discouraged public performances of his own hyper-complex works for many years, essentially cultivating his art in private. In both cases, the pursuit of knowledge (or craft) is seen as something idealistic and unsullied, beyond the dirtiness and compromise of material concerns. Yet in both Kurosawa’s film and DeWitt’s book, the heroes wind up having to make use of their knowledge in a very impure world.

Are there readers who hate The Last Samurai? Probably; no book is universally admired. DeWitt’s style is sometimes overly exuberant, and valuable narrative clues can easily get lost in the flow. There is a lot of Joycean “showing off” in this book. It gets excessive at times. Here are a couple of random pages:

Spending 500 pages with characters who say things like “For as long as I can remember Sib has been pining for Fraser’s Ptolemaic Alexandria (a superb work of scholarship which no home should be without)” is not for everyone. Whole paragraphs in Greek, Icelandic and Japanese are likely to put some readers off, even with translations provided. But there is a great saving grace: the book is often very funny. There’s some memorable high comedy (as well as sadness, and in one case violence) in the scenes where Ludo, after getting past obstacles and gatekeepers, tells the various father figures “I’m your son.” The humor also keeps Ludo from sounding too much like an annoying precocious child, the sort of kid who throws a fit if you misstate the diameter of the moon or refer to a ship as a boat.

Ultimately, like any great or near-great novel, the book stands alone as an aesthetic achievement, and it gives you a lot to ruminate on. The Last Samurai can be read as a defense of classical, humanistic education, or as a critique of it, or as both.3 It’s a great character study of people who are somewhat lost in a world that prizes material success over the pursuit of knowledge. However you want to look at it, here’s one piece of advice: it’s a good idea to watch The Seven Samurai before reading it, if you haven’t already.

Getting the book published was a nightmarish experience for multiple reasons; see here for the full story. DeWitt is not a prolific author, and when the New Directions edition appeared, it meant that she was almost 60 when her first and most famous book became easily available to readers. To complicate things even more, shortly after the first publication of The Last Samurai, a movie with the same title starring Tom Cruise was released, which had no connection to the book. When I recommend the book to people, they sometimes ask me if it’s “what that Tom Cruise movie was based on.”

One thing about the book that rings false is that Sibylla faked her way into Oxford by forging her grades. As far as I know, entry to Oxford as an undergraduate is based on an examination and an interview. Fake grades from an American high school won’t help you.

DeWitt appends an afterword, basically stating that there are a lot more Ludos out there than we think, and reforming our education system would help us find them. This sounds like a banal truism to me, and also beside the point. I really don’t think the book’s importance lies in addressing a social problem, along the lines of The Jungle. It’s too wacky, complex, funny and innovative to be a piece of didactic fiction.

Great review! As I said over on my capsule review of the book, the idea that this book can offer you any advice about any subject besides making interesting art or deepening connections with other human beings seems silly. Sib's pedagogy is not good! Helen DeWitt doesn't seem like someone who could actually help us to discover more Ludos. I mostly saw this book as an allegory about the artistic process, and I don't know any Latin, so I didn't know that Ludo meant "play." I just saw the whole thing as about an artist finding their way through culture and history; just like Kurosawa is always deftly negotiating between the past and present in his films, DeWitt is showing how the classical past has lessons to teach us even in a world mediated by technology.